Awareness | Debate | Action

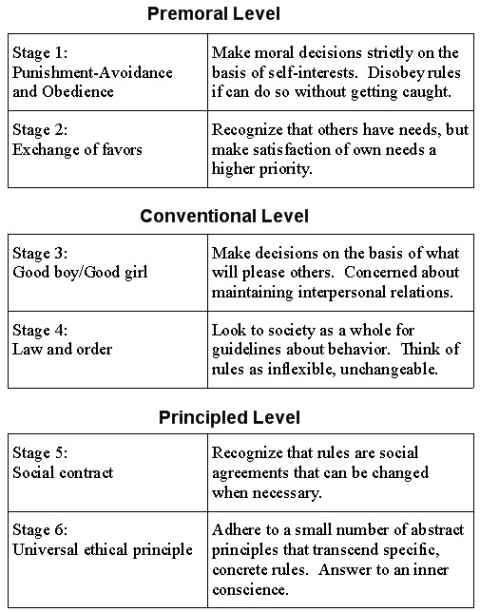

Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development constitute an adaptation of a psychological theory originally conceived of by the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. Kohlberg began work on this topic while a psychology postgraduate student at the University of Chicago in 1958, and expanded and developed this theory throughout his life.

The theory holds that moral reasoning, the basis for ethical behavior, has six identifiable developmental stages, each more adequate at responding to moral dilemmas than its predecessor. Kohlberg followed the development of moral judgment far beyond the ages studied earlier by Piaget, who also claimed that logic and morality develop through constructive stages. Expanding on Piaget's work, Kohlberg determined that the process of moral development was principally concerned with justice, and that it continued throughout the individual's lifetime, a notion that spawned dialogue on the philosophical implications of such research.

Kohlberg relied for his studies on stories such as the Heinz dilemma, and was interested in how individuals would justify their actions if placed in similar moral dilemmas. He then analyzed the form of moral reasoning displayed, rather than its conclusion, and classified it as belonging to one of six distinct stages.

Nevertheless, an entirely new field within psychology was created as a direct result of Kohlberg's theory, and according to Haggbloom et al.'s study of the most eminent psychologists of the 20th century, Kohlberg was the 16th most frequently cited psychologist in introductory psychology textbooks throughout the century, as well as the 30th most eminent overall.

Kohlberg's scale is about how people justify behaviors and his stages are not a method of ranking how moral someone's behavior is. There should however be a correlation between how someone scores on the scale and how they behave, and the general hypothesis is that moral behaviour is more responsible, consistent and predictable from people at higher levels.

Pre-Conventional Morality |

|||

Stage 1 |

Obedience or Punishment Orientation |

This is the stage that all young children start at (and a few adults remain in). Rules are seen as being fixed and absolute. Obeying the rules is important because it means avoiding punishment. |  |

Stage 2 |

Self-Interest Orientation |

As children grow older, they begin to see that other people have their own goals and preferences and that often there is room for negotiation. Decisions are made based on the principle of "What's in it for me?" For example, an older child might reason: "If I do what mom or dad wants me to do, they will reward me. Therefore I will do it." | |

Conventional Morality |

|||

Stage 3 |

Social Conformity Orientation |

By adolescence, most individuals have developed to this stage. There is a sense of what "good boys" and "nice girls" do and the emphasis is on living up to social expectations and norms because of how they impact day-to-day relationships. |  |

Stage 4 |

Law and Order Orientation |

By the time individuals reach adulthood, they usually consider society as a whole when making judgments. The focus is on maintaining law and order by following the rules, doing one's duty and respecting authority. | |

Post-Conventional Morality |

|||

Stage 5 |

Social Contract Orientation |

At this stage, people understand that there are differing opinions out there on what is right and wrong and that laws are really just a social contract based on majority decision and inevitable compromise. People at this stage sometimes disobey rules if they find them to be inconsistent with their personal values and will also argue for certain laws to be changed if they are no longer "working". Our modern democracies are based on the reasoning of Stage 5. |  |

Stage 6 |

Universal Ethics Orientation |

Few people operate at this stage all the time. It is based on abstract reasoning and the ability to put oneself in other people's shoes. At this stage, people have a principled conscience and will follow universal ethical principles regardless of what the official laws and rules are. |

|

Objections to the Kohlberg theory

- Does moral reasoning necessarily lead to moral behaviour? Big difference between knowing what we ought to do versus our actual actions

- Is justice the only aspect of moral reasoning we should consider? Compassion, caring and other interpersonal feelings may play an important part in moral reasoning as well

- Does Kohlberg’s theory overemphasize Western philosophy? Eastern cultures may have different moral outlooks

- Carol Gilligan claims that Kohlberg was biased in his research, as he only surveyed males, and did not females. This would corrupt results because males and females are instilled different beliefs and values according to their sex. For example, males are taught to be independent and abstract, while females are taught to be nurturing, caring and affectionate

-

Comment by Cromag on February 3, 2014 at 10:27pm

-

Jonathan Haidt of New York University and author of The Righteous Mind talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about his book, the nature of human nature, and how our brain affects our morality and politics. Haidt argues that reason often serves our emotions rather than the mind being in charge. We can be less interested in the truth and more interested in finding facts and stories that fit preconceived narratives and ideology. We are genetically predisposed to work with each other rather than being purely self-interested and our genes influence our morality and ideology as well. Haidt tries to understand why people come to different visions of morality and politics and how we might understand each other despite those differences.

Time: 1:03:01Size:28.9 MBRight-click or Option-click, and select "Save Link/Target As MP3.

Comment

© 2025 Created by Cromag.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of The Activist Motivator to add comments!

Join The Activist Motivator